www.lesliehalliwell.com

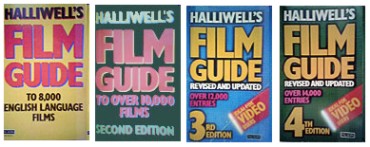

Here's number 4 in an occasional series that reviews unfamiliar or neglected books on film (which of course you can find here at the British Library). Today's choice is Leslie Halliwell's Halliwell's Film Guide (London: Granada, 1977, 2nd ed. 1979, 3rd ed. 1981, 4th ed. 1983, 5th ed. 1985, 6th ed. 1987, 7th. ed. 1989).

At first sight, Halliwell's Film Guide may not seem a suitable choice for an unfamiliar or neglected text, since it is hardly an obscure work in need of championing. It's the one film book that anyone is likely to have (in the UK, at least) if they have just the one film book on their shelves. But as far as I am concerned, there are two Halliwell's Film Guides. One is the work that ran to seven editions and ended in 1989 with its original author's death. The other is the 1396-page behemoth in its umpteenth edition, edited by John Walker from 1991 and David Gritten from 2008. It is the former that has become the neglected work, and which is worth examining once again.

Leslie Halliwell (1929-1989) was, by profession, a buyer of films for television, for the ITV network for much of his career and for his final years the buyer of US films for showing on Channel 4. He had previously been a film writer and cinema manager, and became a household name through his Filmgoer's Companion (first published 1965) and his Film Guide (first published 1977). He wrote several other books on film history.

The original Film Guide listed 8,000 English language films. With successive editions, foreign language and silent films were added, as well as new films. The history of the Guide, its predelictions, omissions and variations, you can read about at www.lesliehalliwell.com. Halliwell was notoriously traditionalist in his tastes (the most recent film to which he awarded one of his coveted four stars was Bonnie and Clyde, from 1967), loathing most of the trends that were to characterise the cinema of the 1970s onwards. Halliwell revered the 30s and 40s, which of course just happened to be the cinema that he knew when growing up, and it is the values of the films from that so-called Golden Age of cinema that determine for Halliwell what cinema should be, and now no longer was.

The Halliwell's Film Guide that we find on the bookshelves now is a bizarre creature, because the greater part of it is still Halliwell's original writing, but the entries for more recent films and patently written by a different hand with diametrically opposed opinions and system of scoring. Films that Halliwell would have decried are now praised to the skies and older films that once he marked down have been revalued, sometimes with a peculiar mix of modern and traditional editors' comments. It makes for a very strange read, and again LeslieHalliwell.com is the place to go if you want to see some of these anomalies analysed.

Cinema has moved on, and the new editors are right to produce something for the readership of today. Eventually, one assumes, they will over-write everything that Halliwell himself originally produced - if they ever have the time to view all those films again. So that's why one has to go back to the sixth edition and before to uncover the original work with its unadulterated authorial mind, and to discover its virtues.

Those virtues are of two kinds. One is the record of a view of cinema from someone with an intelligent knowledge of every aspect of its production, exhibition and social history who grew up in the period when traditional Hollywood was at its height. It is a sometimes curmudgeonly, sometimes nostalgic view, but there is value in the precision with which it sets out its opinions. Cinema was once the ugly upstart that supplanted the theatre and music hall and was representative of all that was vicious about the modern age. Wind forward a few decades, and it is the rosy home of steady virtues (social, technical, artistic) that is in its turn threatened by all that is new.

The second virtue - and that which appeals to me - is in the writing. Ernest Lindgren in his book The Art of the Film (another candidate for a neglected text) writes of the 'single action' or 'plot-theme' which characterises the well-constructed film. He says:

The film ... represents its action as taking place before us while we sit and watch it, and it requires to be viewed in a single sitting ... The story of the most successful kind of film ... will confine itself to the representation of a single action.

Lindgren then says that it is possible "to summarize this central action in the form of a brief statement" and proceeeds to give several examples of classic films whose essence can be boiled down to a line or two that describes the essential action. It is in the writing of the plot-theme of films that Leslie Halliwell achieves greatness. He is the plot summariser par excellence, but it is more than a hack boiling down a work of art to the barest point - it has a particular poetry of its own, and one which none of Halliwell's many imitators has come close to emulating. He reveals the film - one sees it, or recalls seeing it, or feels a great compulsion to go and see it, not because he has said all that there is to say about it but because what he says is a doorway to the film's discovery.

Some of Halliwell's plot summaries are deservedly famous: "Two students marry; she dies" (Love Story); "An egotistic Southern girl survives the Civil War but finally loses the only man she cares for" (Gone with the Wind). But there hundreds if not thousands of examples, which sum up the film with wit and haiku-like insight. Of course, the descriptions are complemented by further comments, where the author's opinions creep in, but it is the plot summaries that are so acute. See if you can identify these films from how he describes them:

- An adventurer's life with the Arabs, told in flashbacks after his accidental death in the thirties.

- A 12-year-old boy, unhappy at home, finds himself in a detention centre but finally escapes and keeps running.

- An English housewife survives World War II.

- A stuffy heiress, about to be married for the second time, turns human and returns gratefully to number one.

- A count organizes a weekend shooting party which results in complex love intrigues among servants as well as masters.

- In old Arizona, the proprietress of a gambling saloon stakes a claim to valuable land and incurs the enmity of a lady banker.

- A beautiful girl is murdered ... or is she? A cynical detective investigates.

- A mysterious stranger helps a family of homesteaders.

- The path of true love is roughened by mistaken identities.

(Answers at the end of this post - and garlands and prizes to anyone who gets the last one)

Of course there is more to film than plot, and more to Halliwell than plot descriptions. It is his opinions that give the book life, and which ultimately send us to see the film or, having seen it, to turn to his option and either agree or argue with him. But in his plot-themes Halliwell shows what makes movies tick. It's like the opening scene in The Player, when the ideas for new film are being sold as one-liners, only there the intention is to boil down folly to its essence. Halliwell shows us, ultimately, how films work. That, along with astute if reactionary opinions that are of his age, make the original Film Guide well worth visiting, and not the door-stopping, muddled hybrid that you will find in the shops today.

Answers:

Lawrence of Arabia, Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows), Mrs Miniver, The Philadelphia Story, La règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game), Johnny Guitar, Laura, Shane, Top Hat