George Percy Churchill’s Biographical Notices of Persian Statesmen and Notables

In 1906, the Government of India Foreign Department published (and republished in 1910) an index of prominent Qajar statesmen, compiled by George Percy Churchill, Oriental Secretary at the British Legation in Tehran. According to Cyrus Ghani, this collection of notes and genealogical tables, entitled Biographical Notices of Persian Statesmen and Notables, is the only document of its kind and serves an ‘indispensible source to ascertain who the British held in high regard and who they considered to be pro-Russian or independent’ (Ghani, pp. 78-79). Indeed, the importance of the work is attested to by numerous references in monographs and in entries in, for example, the invaluable reference tool Encyclopædia Iranica.

Left: 'Biographical Notes' (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746)

Right: 'Biographical Notices of Persian Statesmen and Notables', 1910 (British Library, IOR/L/PS/20/227)

Copies of the Biographical Notices are available in the records of the India Office and Foreign Office held at the British Library and National Archives respectively. Only three further copies appear to be held in libraries at Bamberg, Cambridge and Canberra, though a 1990 translation into Persian is more widely available (Mīrzā Ṣāliḥ, 1990).

Churchill’s Draft Text

However, a little-known manuscript draft of the Biographical Notices exists in the archive of the Bushire Residency, a part of the India Office Records (‘Biographical Notes’, IOR/R/15/1/746), and is now digitised and available online.

Manuscript note in 'Biographical Notes' (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746, f. 3v)

In a signed note (f. 3v), Churchill remarks that he compiled his work from a variety of sources, in particular from Lieutenant-Colonel H. Picot’s, Biographical Notices of Members of the Royal Family, Notables, Merchants and Clergy (1897), which he endeavoured to update and amplify. The draft has the appearance and feel of a scrap-book, with cut-outs of entries from Picot’s work and other printed reports, juxtaposed with up-to-date information written in Churchill’s own hand, as well as seal impressions, signatures, photographs and other elements pasted in.

'Tree of the Royal Kajar House' (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746, ff. 28v-29r)

In addition to the biographical entries, the draft includes an impressive hand-written genealogical ‘Tree of the Royal Kajar House’ (ff. 28v-29r); a list of words used in the composition of Persian titles (ff. 4r-5v); a list of Persian ministers, provincial governors and others receiving Nowruz greetings in 1904 (ff. 33v-34r); and a list of the principal of Persian diplomatic and consular representatives (ff. 30v-31r). Appearing on folios 32v-33r, quite incidentally with notes written on the back, is a seating plan for a dinner of the Omar Kháyyám Club on 23 November 1905.

Seating plan for the Omar Khayyam Club Dinner, 23 November 1905 (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746, ff 32v-33r)

An Abundance of Seals

What stands out most in Churchill’s draft is the abundance of seal impressions – over 300 of them – that appear to have been cut out from Persian correspondence and envelopes. These appear next to the biographical entry of the seal owner, and, in some cases, a single entry is accompanied by multiple seal impressions reflecting the use of different seal matrices at different dates and containing personal names or official and honorific titles. In addition, there are three clusters of seal impressions that are not associated with specific biographical entries, and these include seals of Qajar rulers, such as Fath ‘Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834) and Muhammad Shah (r. 1834-1848), as well as other Qajar statesmen.

Draft entry and print entry for Arfa' ud-Daulah (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746, f. 66v; IOR/L/PS/20/227, p. 10)

Entry for Mirza ʻAli Asghar Khan Amin us-Sultan in 'Biographical Notes' (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746, f. 55r)

Seals Set within Illuminated Frames

Two clusters of seal impressions on folios 2v and 29v contain three examples of seals set in ornately decorated illuminated frames that have been cut out from firmans of Farmanfarma Husayn ‘Ali Mirza, Governor-General of Fars, dated 1229 AH (1813/14 CE). This art form developed in Iran during the later Safavid and Qajar eras, spreading throughout the Islamic world. Annabel Gallop and Venetia Porter note such illuminated framed seals with ‘their own architectural constructs’ or else ‘nestling within a bed of petals, sitting at the heart of a golden flame or sending forth rainbow-hued rays’ (pp. 170-172).

Seal impressions on folios 2v (left) and 29v (right) from 'Biographical Notes' (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746)

Embossed Seals and Printed Stationery

The other cluster of cut-outs found on folio 3r are in fact not ink seal impressions, but impressions of embossed (blind-stamped) seals and decorative printed letterheads of specially-printed stationery. These are variously dated and include those of Amin al-Dawlah and Mas‘ud Mirza Zill al-Sultan, and contain decorative symbols such as laurel reefs, crowns, and the lion and sun national emblem (shir u khurshid).

A collection of embossed and printed seals in 'Biographical Notes' (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746, f. 3r)

Embossed seals made with metal presses came into use in Europe in the latter part of the eighteenth century mainly among companies and institutions, but also by individuals. In the nineteenth century, this practice had become widespread in Ottoman bureaucracy. This collection, taken together with seal presses in museum collections in Iran (Jiddī, p. 75), demonstrates that the practice had become well-established in Qajar administration. Moreover, the embossed seals juxtaposed with traditional ink seal impressions in this volume point towards the ‘changing relations of production and advancing commercialization’ as a result of colonialism and globalisation that affected Islamic diplomatics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Messick, pp. 234-235). Indeed, it has been noted that such embossed seals appeared at around the same time as other developments, such as the widening use of printed letterheads and rubber stamps (Gallop and Porter, p. 122).

Photographic Images

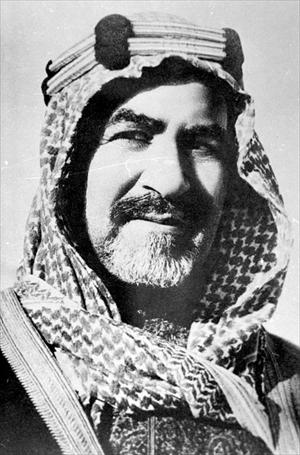

A number of the biographical entries are also accompanied by photographs of the subject in official dress. These are found on folio 48 for Mirza ‘Ali Asghar Khan Amin al-Sultan; two cut out photographs of Hakim al-Mulk Mirza Mahmud Khan and one of Hakim al-Mulk Ibrahim Khan on folio 114v; and one of Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1896-1907) on folio 163v.

Photographs found in 'Biographical Notes' (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/746)

The Importance of Churchill’s Work

In one sense, Churchill’s work represents an important work in the context of British colonial knowledge of the political landscape of Qajar Iran at the beginning of the twentieth century. Yet, as has been noted by Gallop and Porter (p. 154), the presence of an abundance of seal impressions reflects the keen eye of an enthusiastic collector. However, we should not necessarily view collecting and colonial intelligence gathering as mutually exclusive fields. As Carol A. Breckenridge has noted: ‘The world of collecting was considerably expanded in the post-enlightenment era. With the emergence of the nineteenth-century nation-state and its imperializing and disciplinary bureaucracies, new levels of precision and organization were reached. The new order called for such agencies as archives, libraries, surveys, revenue bureaucracies, folklore and ethnographic agencies, censuses and museums. Thus, the collection of objects needs to be understood within the larger context of surveillance, recording, classifying and evaluating’ (p. 195-96).

Indeed, seal impressions were collectable not only as objects of Orientalist curiosity and research, but also as the preeminent symbol of personal and political authority, power and hierarchy, as well as ownership. Although Churchill’s collection of seal impressions was absent from the final printed version of the Biographical Notices, the draft text provides researchers with a valuable source for the study of Qajar seals and sealing practices at the turn of the twentieth century, at a time in which the Islamic seal was being replaced by other instruments of textual and visual authority, such as embossed seal and photographs.

Primary Sources

British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, ‘Biographical Notes’, IOR/R/15/1/746

British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, ‘Biographical notices of Persian statesmen and notables’, IOR/L/PS/20/227

British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, ‘Persia: biographical notices of members of the royal family, notables, merchants and clergy’, Mss Eur F112/400

The National Archives (TNA), ‘PERSIA: Biographical Notices. Persian Statesmen and Notables’, FO 881/8777X and FO 881/9748X

Further Reading

Carol A. Breckenridge, ‘The Aesthetics and Politics of Colonial Collecting: India at the World Fairs’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 31, No. 2 (April, 1989), pp. 195-216

Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, New York, 1996-

Cyrus Ghani, Iran and the West: A Critical Bibliography (London: Kegan Paul International, 1987)

Annabel Teh Gallop and Venetia Porter, Lasting Impressions: Seals from the Islamic World (Kuala Lumpur, 2012)

Muḥammad Javād Jiddī (trans. M. T Faramarzi), Muhrhā-yi salṭanatī dar majmūʻah-i Mūzih-i Kākh-i Gulistān [Royal seals in Golestan Palace Museum collection] (Tihrān, 1390 [2011])

Brinkley Messick, Calligraphic State: Textual Domination and History in a Muslim Society (Berkley, 1993)

George Percy Churchill (trans. Ghulām Ḥusayn Mīrzā Ṣāliḥ), Farhang-i rijāl-i Qājār (Tihrān, 1369 [1990])

Daniel A. Lowe, Arabic Language and Gulf History Specialist (@dan_a_lowe)