The legend

of Phra Malai, a Buddhist monk of the Theravada tradition said to have attained

supernatural powers through his accumulated merit and meditation, is the main

text in a nineteenth-century Thai folding book (samut khoi) held in the Thai, Lao and Cambodian Collections (Or.

16101). Phra Malai

figures prominently in Thai art, religious

treatises, and rituals associated with the afterlife,

and the story is one of the most popular subjects

of nineteenth-century illustrated Thai manuscripts. The earliest surviving examples of

Phra Malai manuscripts date back to the late eighteenth century, although it is

assumed that the story is much older, being based on a Pali text. The legend also has some parallels with

the Ksitigarbha Sutra.

The Thai text in this

manuscript is combined with extracts in Pali from the

Abhidhammapitaka, Vinayapitaka, Suttantapitaka, Sahassanaya,

and illustrations from the Last Ten Birth Tales of the Buddha (Thai thotsachat).

Altogether, the manuscript has 95 folios with illustrations on 17 folios. It

was very common to combine these or similar texts in one manuscript, with Phra Malai

forming the main part. These texts are written in

Khom script, a variant of Khmer script often used in Central Thai religious

manuscripts. Although Khom script, which was regarded as sacred, was normally

used for texts in Pali, in the Thai manuscript tradition, the story of Phra Malai

is always presented in Thai. Because Khmer script was not designed for a tonal language like Thai,

tone markers and certain vowels that do not exist in Khmer script have been

adopted in Khom script to support the proper Thai pronunciation and intonation.

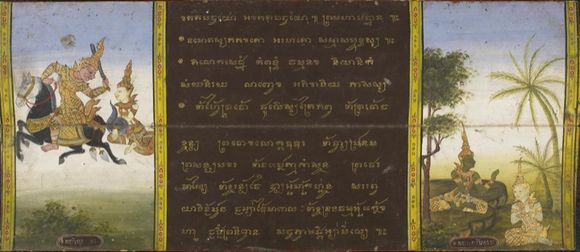

Vidura and Vessantara Jatakas (Or 16101, folio 6)

Most of the text is in black ink on

paper made from the bark of the khoi tree (streblus asper). However, the text

accompanying the illustrations of the Last Ten Birth Tales is written in gold

ink on blackened khoi paper, emphasizing the importance of these Jatakas

symbolising the ten virtues of the Buddha. Gold ink, as well lavish

gilt and lacquered covers, added value and prestige to the manuscript, which

was commissioned on occasion of a funeral service. The commission

and production of funeral presentation volumes was regarded as a way of earning merit on behalf of the

deceased.

Other miniature paintings depict the

Buddha in meditation, scenes from the life of

Phra Malai, as well as genre scenes of lay people. According to a colophon in

Thai script on the first folio, the manuscript is dated 2437 BE (AD 1894).

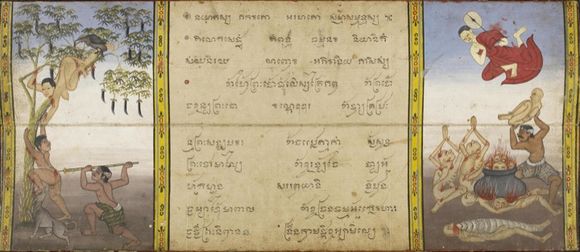

Phra Malai visiting hell (Or 16101, folio 8)

During his visits to hell (naraka),

Phra Malai is said to bestow mercy on the creatures suffering there. They

implore him to warn their relatives on earth of the horrors of hell and how

they can escape it through making merit on behalf of the

deceased, meditation and by following Buddhist precepts.

Although the subject of hell is mentioned in the Pali canon

(for example, in the Nimi Jataka, the Lohakumbhi Jataka, the Samkicca

Jataka, the Devaduta Sutta, the Balapanditta Sutta, the Peta-vatthu etc.) the legend of Phra

Malai is thought to have contributed significantly to the idea of hell in Thai society.

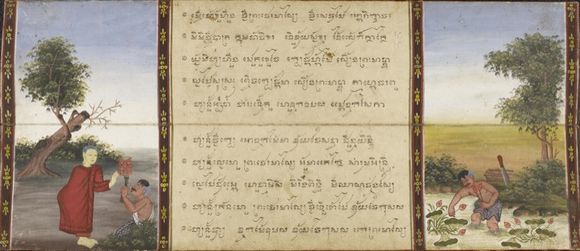

Back in the human realm, the monk receives an

offering of eight lotus flowers from a poor woodcutter, which he eventually

offers at the Chulamani Chedi, a heavenly stupa believed to contain a

relic of the Buddha. In Tavatimsa heaven, Phra Malai converses with the god

Indra and the Buddha-to-come, Metteyya, who reveals to the monk insights about

the future of mankind.

Lotus offering scene, Or 16101, folio

28

Through recitations of Phra Malai the karmic effects

of human actions were taught to the faithful at funerals and other merit-making

occasions. Following Buddhist precepts, obtaining

merit, and attending performances of the

Vessantara Jataka all counted as virtues that increased the chances of a

favourable rebirth, or Nirvana in the end.

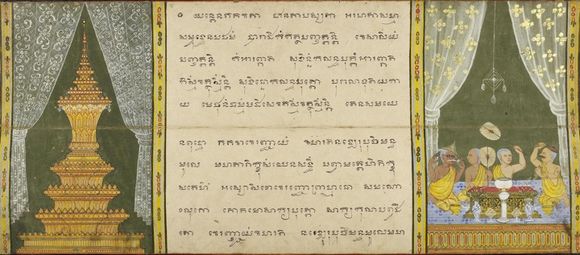

Illustrated

folding books were produced for a range of different purposes in Thai Buddhist

monasteries and at royal and local courts. They served as handbooks and

chanting manuals for Buddhist monks and novices. Producing folding books or

sponsoring them was regarded as especially meritorious. They often, therefore,

functioned as presentation volumes in honor of the deceased. It comes as no

surprise that this manuscript contains an illustration of a lavishly decorated

coffin attended by two Buddhist monks who are trying to fend off two ‘fake’

monks.

Funeral scene (Or

16101, folio 92)

Traditionally, Thai monks reciting

the legend of Phra Malai would embellish and dramatise their performances,

contrary to their strict behavioural rules. By the end of the nineteenth

century, monks were officially banned from such performances. As a result, retired

or ‘fake’ monks often delivered the popular performances, unconstrained by the

rules of the Sangha.

A full text digital copy of Or 16101 can be viewed online at British Library Digitised Manuscripts.

Lacquered front cover with gilt flower ornaments (Or

16101)

Further reading

There is an

excellent translation from Thai into English of the entire legend of Phra Malai

by Bonnie Pacala Brereton, which is included in her book Thai Tellings of

Phra Malai – texts and rituals concerning a Buddhist Saint. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona

State University, 1995

Chawalit, Maenmas (ed.): Samut khoi. Bangkok: Khrongkan

suepsan moradok watthanatham Thai, 1999

Ginsburg,

Henry: Thai art and culture: historic manuscripts from Western Collections.

London: British Library, 2000

Ginsburg,

Henry: Thai manuscript painting. London: British Library, 1989

Igunma,

Jana: ʻAksoon Khoom - Khmer heritage in Thai and Lao manuscript cultures.ʼ

In: Tai Culture Vol. 23. Berlin : SEACOM, 2013

Igunma, Jana: ʻPhra Malai - A Buddhist Saint’s Journeys to

Heaven and Hell.ʼ

Peltier, Anatole: ʻIconographie de la

légende de Braḥ Mālay.ʼ BEFEO, Tome LXXI (1982), pp. 63-76

Wenk, Klaus: Thailändische Miniaturmalererien nach einer

Handschrift der Indischen Kunstabteilung der Staatlichen Museen Berlin.

Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner, 1965

Zwalf, W. (ed.): Buddhism: art and faith. London:

British Museum Publications, 1985

Jana Igunma, Asian and African Studies