Those of you who have spent a great deal of time on our Digitised Manuscripts site may have encountered the occasional instance of a detached binding amongst the wonderful array of medieval manuscripts on offer. Many of the bindings are spectacular works of art in themselves, featuring amazing examples of medieval embroidery, leatherwork, or ivories. Besides being beautiful to look at, these bindings are also vitally important to scholars investigating the history of the manuscripts they were once attached to.

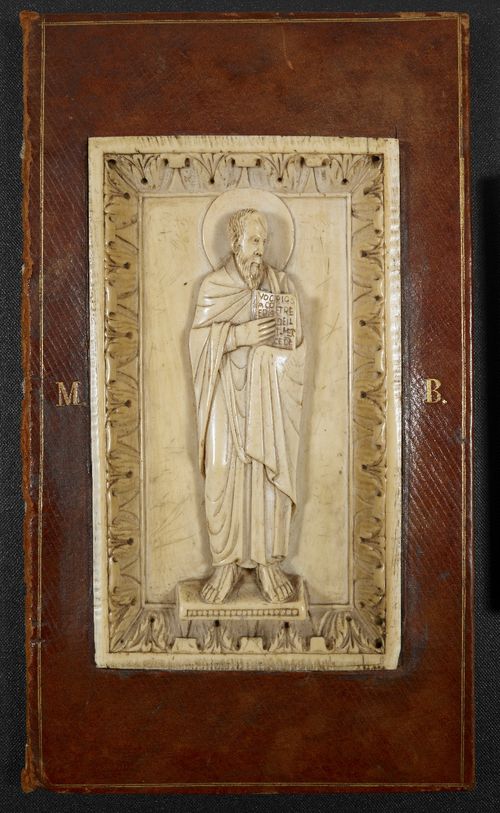

Detached binding containing an ivory plaque of St Paul, from the Siegburg Lectionary, 11th century, Harley MS 2889/1

Bindings can be detached for any number of reasons. It was a policy among many collectors and institutions in the 18th and 19th centuries (the British Museum included) to automatically rebind every newly-arrived manuscript, and unfortunately many of the original bindings from this period are now lost to us. Of course, this is no longer our procedure, and the British Library makes every effort to maintain the integrity of the manuscripts that come to us. Bindings are only replaced these days when it is necessary for preservation or conservation purposes.

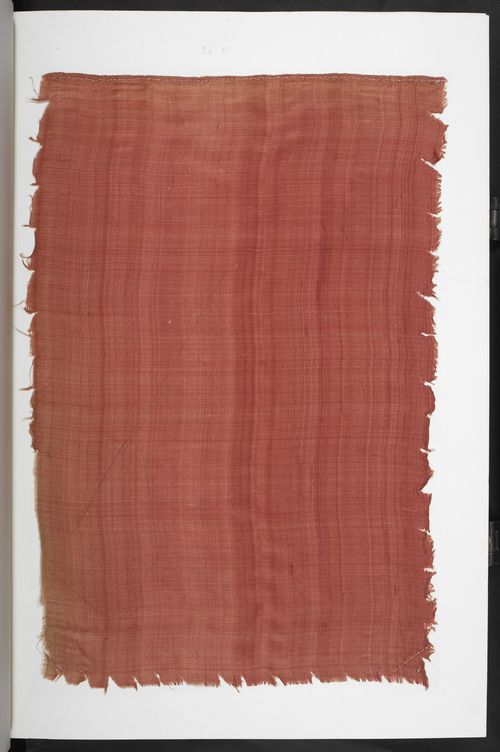

Detached silk curtain, formerly covering a miniature, from the Bedford Psalter and Hours, 15th century, Add MS 42131/1

Because these detached bindings are usually kept in our manuscripts store under the same shelfmark as their erstwhile interiors, there was initially no good way to display them on Digitised Manuscripts, save a wonky workaround in which the images were numbered as end flyleaves. This at least allowed the images to be displayed, but we were aware of the potential for confusion for those interested in examining the bindings themselves, so we’ve been working to develop a better solution. And at long last, here it is: we have created new shelfmarks for a number of the detached bindings, and have republished many of the images online accordingly. We still have a few more to go, and we should issue one caveat – this new system does not incorporate all of the detached bindings in the Library’s collections, only those for select and restricted manuscripts on Digitised Manuscripts. As always, if you have any questions or would like to examine any of these bindings, please get in touch with the Manuscripts Reading Room at [email protected].

Our newly republished manuscripts and detached bindings are below; we hope you enjoy browsing through them!

Add MS 37768: the Lothar Psalter, Germany (Aachen) or France (Tours), 9th century

Add MS 37768/1: detached ivory carving from the cover of the Lothar Psalter, 9th century

Add MS 42130: the Luttrell Psalter, England (Lincolnshire), 1325-1340

Add MS 42130/1: box and volume containing the detached former binding and flyleaves of the Luttrell Psalter, England (Cambridge), c. 1625-1640

Add MS 42131: the Bedford Psalter and Hours, England (London), 1414-1422

Add MS 42131/1: detached former bindings, paste-downs, spines, and silk curtains from the Bedford Psalter and Hours, England, 15th – 17th centuries

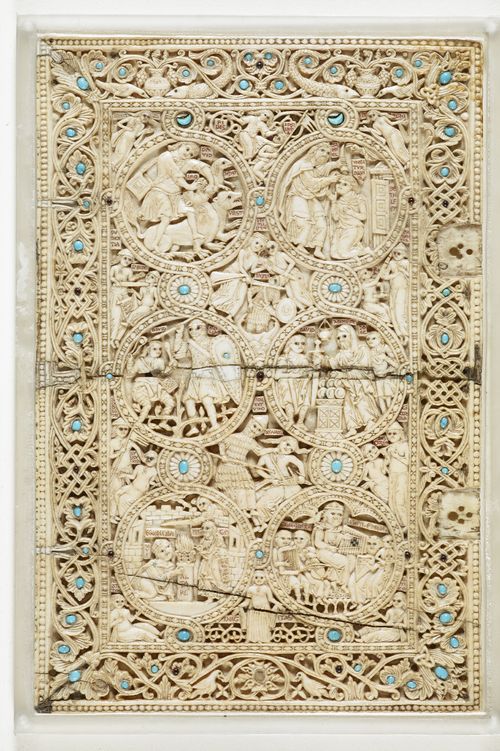

Egerton MS 1139: the Melisende Psalter, Eastern Mediterranean (Jerusalem), 1131-1143

Egerton MS 1139/1: detached binding with ivory panels & backings, wooden panels and metal plates from the Melisende Psalter, 12th century (with later additions)

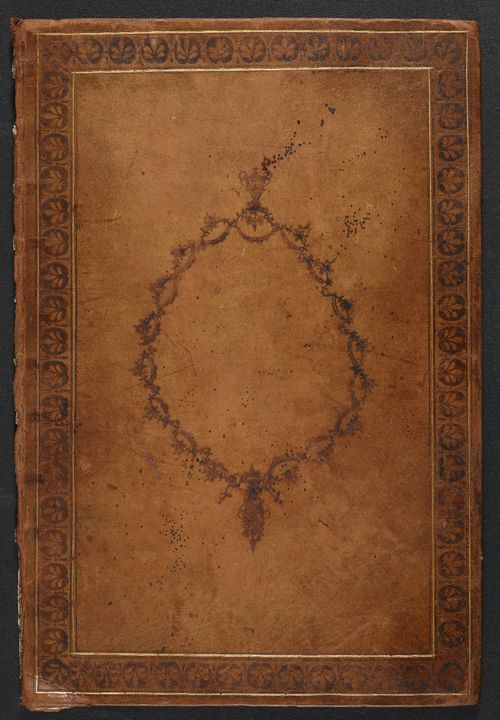

Egerton MS 3277: the Bohun Psalter and Hours, England (London?), second half of the 14th century

Egerton MS 3277/1: detached binding from the Bohun Psalter and Hours, 18th century

Harley MS 603: the Harley Psalter, England (Canterbury), first half of the 11th century

Harley MS 603/1: detached binding and flyleaves from the Harley Psalter, 19th century

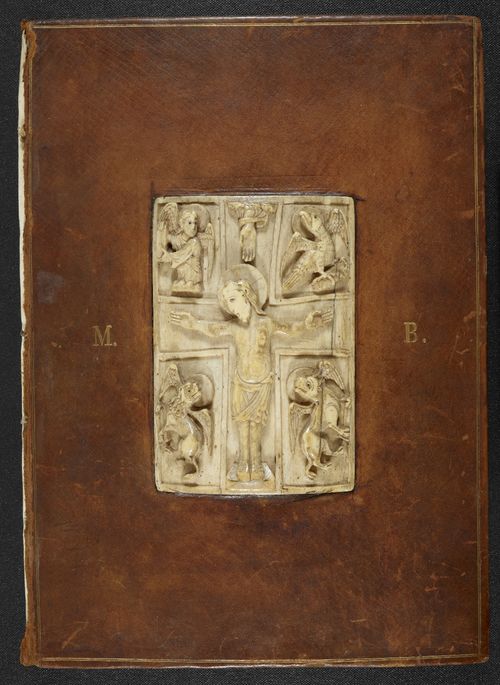

Harley MS 2820: the Cologne Gospels, Germany (Cologne), fourth quarter of the 11th century

Harley MS 2820/1: detached binding from the Cologne Gospels with an ivory panel of the Crucifixion, late 11th century (set in a post-1600 binding)

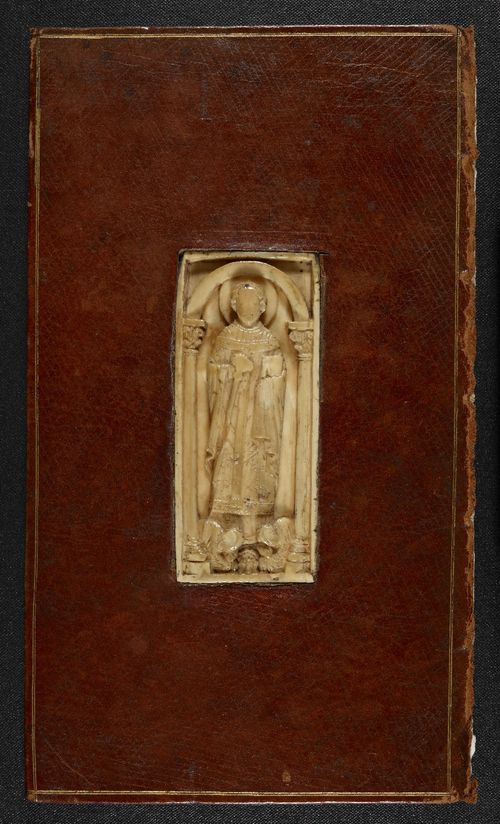

Harley MS 2889: the Siegburg Lectionary, Germany (Siegburg), 11th century

Harley MS 2889/1: detached binding from the Siegburg Lectionary, with two 11th century ivory plaques (set in a 19th century binding)

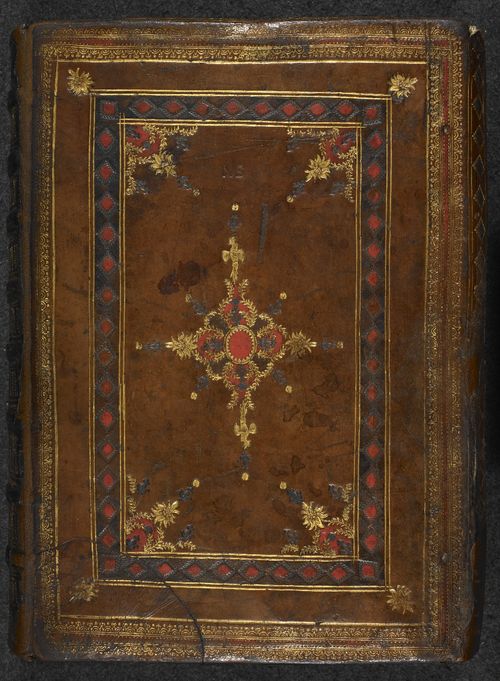

Royal MS 12 C VII: Pandolfo Collenuccio’s Apologues and Lucian of Samosata, Dialogues, Italy (Rome and Florence), 1509 – c. 1517

Royal MS 12 C VII/1: detached chemise binding embroidered with the badge and motto of Prince Henry Frederick (1594-1612)

Update (3 June 2014):

We've just added three more detached bindings to Digitised Manuscripts. And here they are!

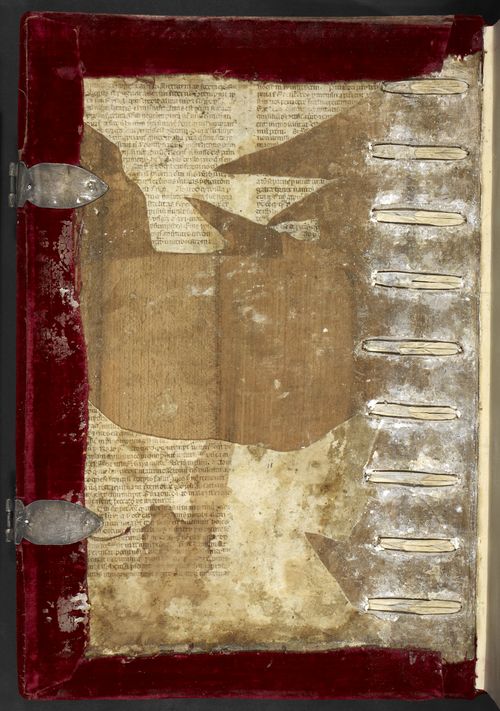

Add MS 18850: the Bedford Hours, France (Paris), c. 1410 - 1430

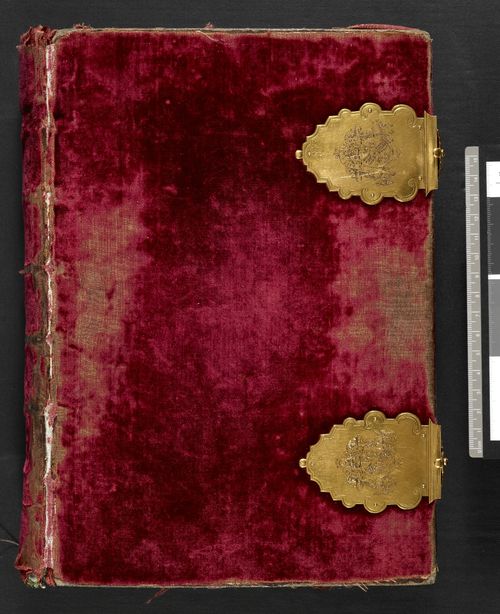

Add MS 18850/1: detached former binding for the Bedford Hours, consisting of a wooden box, 2 red velvet covers with metal clasps and 4 folios, England, 17th century

Add MS 42555: the Abingdon Apocalypse, England, 3rd quarter of the 13th century

Add MS 42555/1: detached former binding components from the Abingdon Apocalypse, 18th century

Add MS 61823: the Book of Margery Kempe, England (East Anglia?), c. 1440

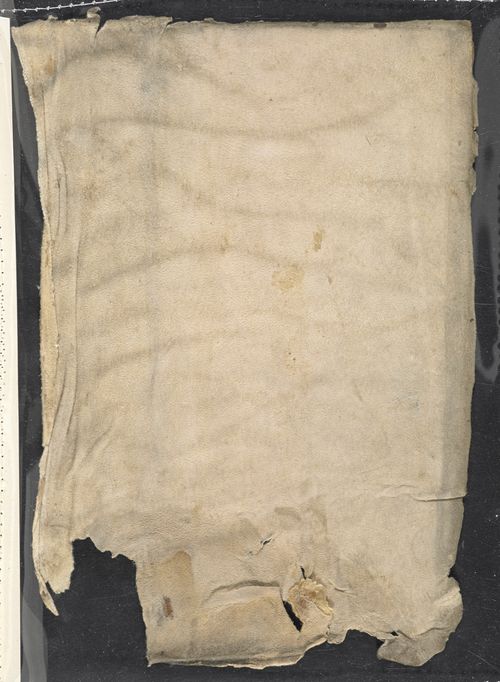

Add MS 61823/1: remains of the original white tawed leather chemise binding from the Book of Margery Kempe, England, c. 1440

- Sarah J Biggs