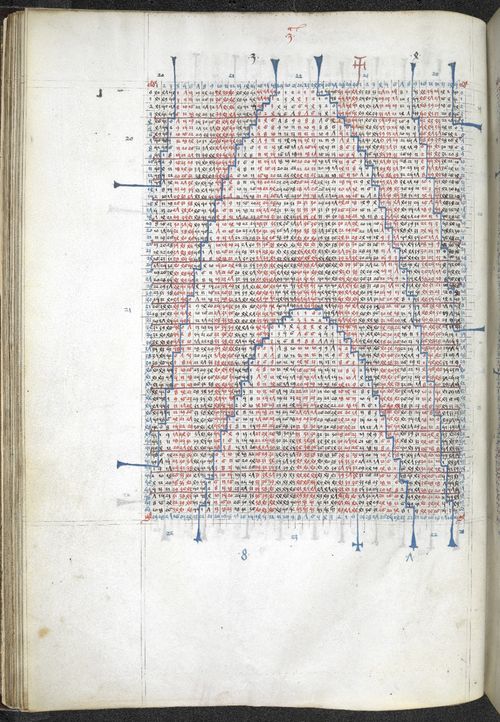

Astronomical table of John Killingworth, from a compilation of astrology and prophecy, England (London?), 1490, Arundel MS 66, f. 29v

Arundel MS 66 is a massive manuscript containing a highly

sophisticated collection of astronomical and astrological works. It combines texts on judicial astrology and

geomancy with astronomical tables, which were necessary tools to calculate the movements

of the planets and stars. As a comprehensive guide to techniques of forecasting

the future, it also contains an interesting selection of English political

prophecies.

Although its early provenance is

untraceable, it has long been suggested that Henry VII was the original patron or recipient of the codex, based largely

on the royal portrait and arms

included in a miniature on f. 201r (see below), as well as several heraldic badges incorporated

in borders, initials and miniatures throughout the text.

Detail of a miniature of Henry VII, surrounded by his courtiers, overseeing an

astrologer making a prediction for the forthcoming year, at the beginning of a treatise on the Revolution of the year of the world, from a compilation of astrology and prophecy, England (London?), 1490, Arundel MS 66, f. 201r

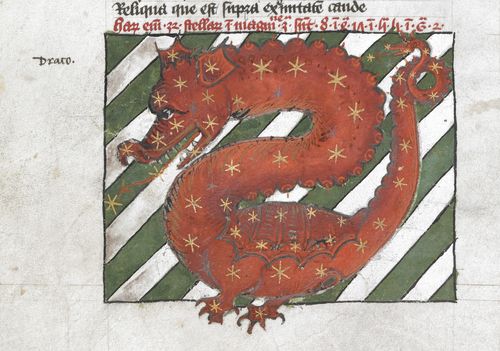

Amongst the elements that can be tied to

Henry VII and his family is the friendly Red Dragon of Cadwaladr, painted against the

Tudor livery colours of white and green; you may remember this miniature from the

opening displayed during the Royal Exhibition. This stand-out Red Dragon was

used in Arundel MS 66 in the place of the more usual image of the constellation Draco, in a section containing Ptolemy's

'Catalogue of Stars'.

Detail of the constellation Draco, at the beginning of Ptolemy's Catalogue of Stars, from a compilation of astrology and prophecy, England (London?), 1490, Arundel MS 66, f. 33r

The main

text in this manuscript is the Decem tractatus astronomiae (or Liber

Astronomiae), a popular handbook

of astrology composed by the famous Italian

astrologer Guido Bonatti of Forli

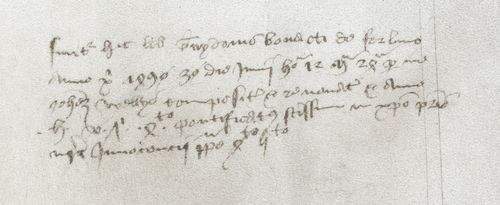

(1207-1296). An otherwise blank leaf at the end of this text bears a note by the

scribe, John Wellys, which may give some insight into the production of the

book.

Detail of John Wellys' note at the end of Guido Bonatti's Decem tractatus astronomiae, from a compilation of astrology and prophecy, England (London?), 1490, Arundel MS 66, f. 249r

The note

reads:

'Finitur hic liber Guydonis

Bonacti de Forlivio anno Christi 1490 30 die junij hora 12 minuta 24a per me

Johannem Wellys compositus et renovatus et anno H. r. 7. 4to pontificatus

sanctissimi in Christo patris nostri Innocenti pape 4to [sic for 8to] 5to'.

Which translates to:

This

book by Guido Bonacti of Forlì was finished

in the year of Christ 1490, on the 30th day of June, 12 hours and 24

minutes, compiled and brought up-to-date by me

John Wellys in the 4th year of K[ing] H[enry] vii and in the 5th

year of the holy pontificate in Christ of our father pope Innocent IV [sic for

VIII].

Whether John Wellys was a trained astrologer or not, he dated the terminus of his work with an extraordinary precision

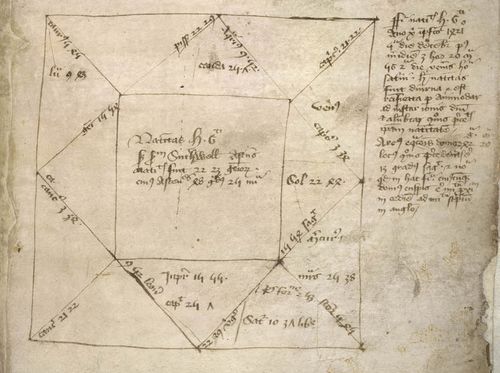

which reminds one of the language often used in astrological charts. Another good

example can be found in Egerton MS 889, which describes the birth date of Henry

VI in a similarly detailed way: 'Nativitas Henrici sexti anno Christi

imperfecto 1421°, 5a die Decembris post meridiem, 3 horam 20m 56s, die Veneris,

hora Saturni (Nativity of Henry VI in the imperfect year of Christ 1421, 5th

day of December, in the afternoon, at 3 hours 20 minutes and 56 seconds, on the

day of Venus, in the hour of Saturn).

Diagram of the horoscope for the birth of Henry VI, from an astronomical and astrological compendium (the 'Codex Holbrookensis'), England (Cambridge), between c. 1420 and 1437, Egerton MS 889, f. 5r

In his note in Arundel MS 66, Wellys also scrupulously calculated

the regnal years of Henry VII and Innocent VIII. Both

the king and the pope came into power in August, in 1485 (22 August) and 1484

(29 August), respectively. Arundel MS 66 was completed in June of 1490,

therefore in the fourth year of Henry's reign and the fifth year of Innocent's pontificate.

John Wellys's inscription, jotted down on a blank leaf,

appears to be more an informal note than an polished colophon. What, then, was

its purpose, and what does this note tell us about the scribe's work? The way

Wellys used verbs is somewhat striking. He preferred to describe his activity

as 'componere' (to put together or

arrange) rather than the more commonly used 'scribere' (to write), implying that his task involved a work of

compilation. He also stressed the fact that he brought the text up to date ('renovatus'). Indeed, a closer look at

Wellys's rendering of Bonatti's Liber

astronomiae shows a great deal of editorial work. The scribe introduced his

own division of the text into not six but seven parts and therefore had to

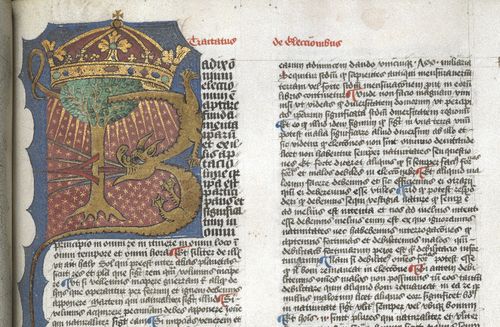

alter Bonatti's preface. In the Tractatus

de Electionibus, one of the tracts forming the Liber astronimiae, his

ingenuity went even further. Wellys was clearly transcribing his text from an

imperfect model. The Tractatus in question contains several gaps and an

imperfect beginning.

Detail of the imperfect beginning of Tractatus de Electionibus, with a miniature of Henry VII’s badge of a crowned tree, from a compilation of astrology and prophecy, England (London?), 1490, Arundel MS 66, f. 129r

Wellys did not bother with the two chapters missing at

the beginning of the tract, instead simply electing to open with chapter 3. However, a

large portion missing at the end seems to have caught his attention. By this

point in his labours he was working on royal commission, which may have had

something to do with his diligence! Not having another copy of

Bonatti's book at hand, Wellys decided to find the missing text elsewhere. On

ff. 143v-147v, he seamlessly replaced Bonatti's text on elections with an

extract from a similar work, De iudiciis astrorum (On the judgements of the

stars) by the Arabic author Haly ibn Ragel. Did King Henry ever notice the difference?

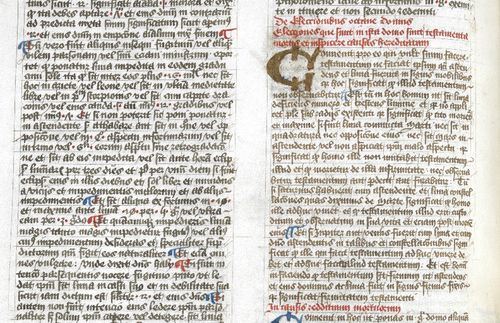

Detail of the incipit of Haly

ibn Ragel's De iudiciis astrorum

interpolated into Guido Bonatti's Tractatus de Electionibus, with the change of ink colour marking the beginning of the

interpolation, from a compilation of astrology and prophecy, England (London?), 1490, Arundel MS 66, f. 143v

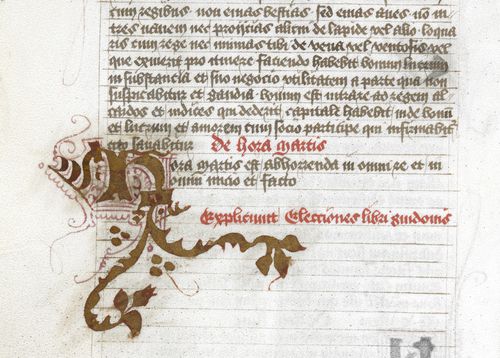

To cover up his textual replacement, Wellys provided an inaccurate rubric at the end of the interpolated passage, which reads, 'expliciunt electiones

libri Guidonis' (here ends the elections of Guido's book).

Detail of the explicit of Haly

ibn Ragel's De iudiciis astrorum

interpolated into Guido Bonatti's Tractatus de Electionibus, from a compilation of astrology and prophecy, England (London?), 1490, Arundel MS 66, f. 147v

Wellys copied part of the replacement text in an added

quire, in a different colour of ink from the rest of the manuscript. He used the same light brown ink to supply

the last two rubrics of the Tractatus de ymbribus

et aeris, the last tract of Bonatti's book (f. 248r), possibly during the same campaign of

revisions. If not for his unusually

worded colophon-note, I would have never discovered John Wellys's trick!

- Joanna Fronska

This post is based on my forthcoming

article 'The

Royal Image and Diplomacy: Henry VII’s Book of Astrology (British

Library, Arundel MS 66)' in the Electronic British Library Journal.

Follow us on Twitter: @blmedieval.