It is not often that our medieval manuscript curators have the opportunity to work on any material that concerns the Americas, but it does occasionally happen. While we were preparing for the recent upload of Add MS 33733, we came across one miniature within that volume that contains a remarkable, if troubling, view of the New World and its inhabitants.

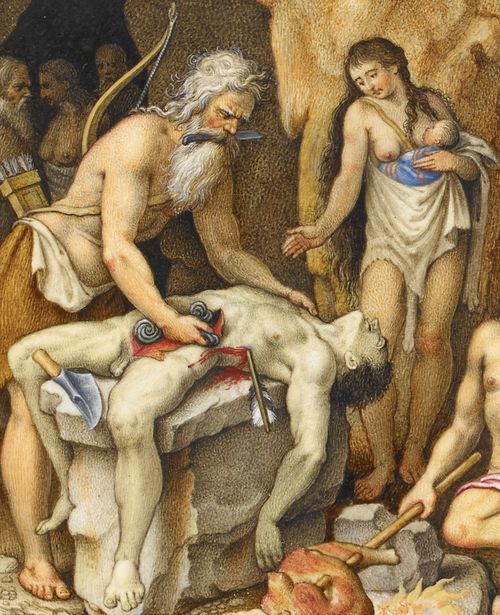

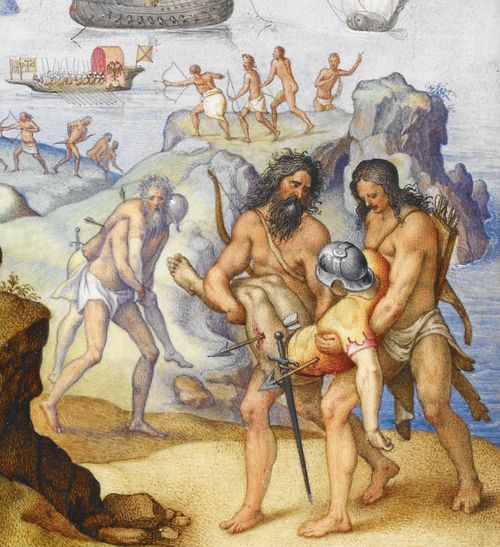

Detail of a miniature of cannibals attacking the members of a Spanish expedition to America in 1530, Add MS 33733, f. 10r

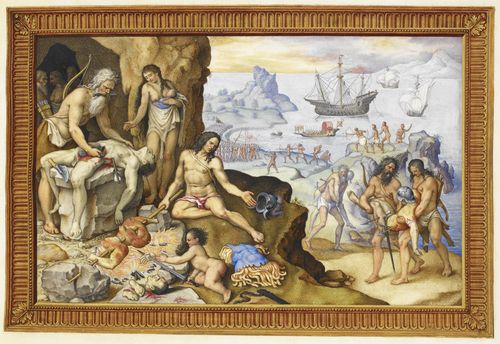

Add MS 33733 is more commonly known as The Triumphs of Charles V. It is made up of a series of 12 miniatures illustrating episodes from the reign of Emperor Charles V of Spain (1500-1558), accompanied by quatrains in Spanish explaining each scene. It was possibly produced for Philip II, the son of Charles V and King of Spain and Portugal (1527-1598), and dates from the 3rd quarter of the 16th century. For many years the exquisite miniatures in the Triumphs were attributed to Giorgio Giulio Clovio (1498-1578), a noted Croatian artist who spent most of his working life in Italy and was active in the same circles as Michelangelo. Recent scholars, however, believe it is more likely that the paintings were produced by a follower or pupil of Clovio, who based his work on a series of engravings published in Antwerp in 1556 by Hieronymus Cock. Whatever the artist’s name might have been, the illuminations he created throughout the manuscript are both impressively executed and breathtakingly detailed. He was clearly inspired by the momumental painting style of the era, even going so far as to include a suitable gilt frame around each miniature.

Detail of a miniature of the Duke of Cleves submitting to Charles V, from the Triumphs of Charles V, Italy or the Netherlands, c. 1556-c. 1575, Add MS 33733, f. 12r

Considering the title of the manuscript, it is unsurprising that the majority of the illuminations depict a notable moment of military or political triumph for the Emperor Charles V (see above). But one seems to be an outlier. On f. 10r can be found the miniature below, an illustration of a Spanish expedition to America in 1530.

Detail of a miniature of cannibals attacking the members of a Spanish expedition to America in 1530, from the Triumphs of Charles V, Italy or the Netherlands, c. 1556-c. 1575, Add MS 33733, f. 10r

This disquieting scene is accompanied by a quatrain on the facing folio (f. 9v), which reads:

Los Indios que hasta aquí de carne humana / Pacían como fieros y indomados / Con virtud y con fuerça soberana / Los veys por César ya domesticados.

A very loose translation: ‘The Indians, who until now had gorged themselves on human flesh like wild and untamed beings, by the virtue and sovereign power of Charles have been domesticated’.

The association of native Americans with cannibalism goes back to nearly the first moment of European contact with these lands. In fact, the very word ‘cannibal’ itself is derived from ‘Canib’ (or 'Carib'), the name of a tribe of people who lived in the West Indies at the time of Columbus’ arrival. In his diary Columbus recorded that the neighbouring Taino people ‘have said that they are greatly afraid of the Caniba’. Several historians have pointed out that Columbus’ use of the word ‘said’ could charitably be described as problematic, since most of his communication with indigenous peoples was carried out through hand gestures, but later attempts at armed resistance on the part of the Caniba solidified his opinion of them as nearly-inhuman savages.

Detail of a miniature of cannibals attacking the members of a Spanish expedition to America in 1530, Add MS 33733, f. 10r

In a 1494 despatch to the Spanish court, Columbus advocated the enslavement of ‘these cannibals, a people very savage and suitable for the purpose, and well-made and of good intelligence.’ Queen Isabella agreed, and in 1503 declared that any of the ‘said cannibals’ who resisted Spanish authority or conversion to Christianity could be legally taken as slaves by the conquistadors. This provided a significant incentive for the conquering Spaniards to describe any newly-encountered people as savages and cannibals, and gory descriptions of these ‘inhuman’ tribes and their practices abound in their accounts.

Detail of a miniature of cannibals attacking the members of a Spanish expedition to America in 1530, Add MS 33733, f. 10r

Isabella’s edict was reconfirmed by a number of subsequent rulers of Spain, including Charles V himself. Enslavement was viewed as a fitting punishment for those intransigent enough to refuse either conquest or conversion, but it was also considered beneficial for the slaves themselves, who could be civilized and saved from eternal damnation. With this in mind, it becomes clear why the scene of carnage above would have been viewed by his contemporaries as one of Charles V’s ‘triumphs’. It is disturbing to think that the subjugation and near-annihilation of an entire race of people could have become an object of royal pride, but it did. We sometimes describe certain of our manuscripts as having ‘long shadows’, reaching back into the past and still touching us today; this one casts a longer shadow than most.

- Sarah J Biggs